The Allure and Elusiveness of Meaning, Identity, and Belonging

An Engagement with Dr. Glenn Loury's Recent Memoir

I have long made the suggestion—not necessarily on this Substack but in conversation elsewhere—that a book is an experience. It is a way to inhabit someone else’s world for a while, or at least their head. In this sense, experimental narrative and argumentative structures—while they can be obnoxious or tedious—are mostly a good thing: we don’t always experience this life, or even our own mind, linearly, and so it is good to have books and other stories that mirror some of the disjointedness.

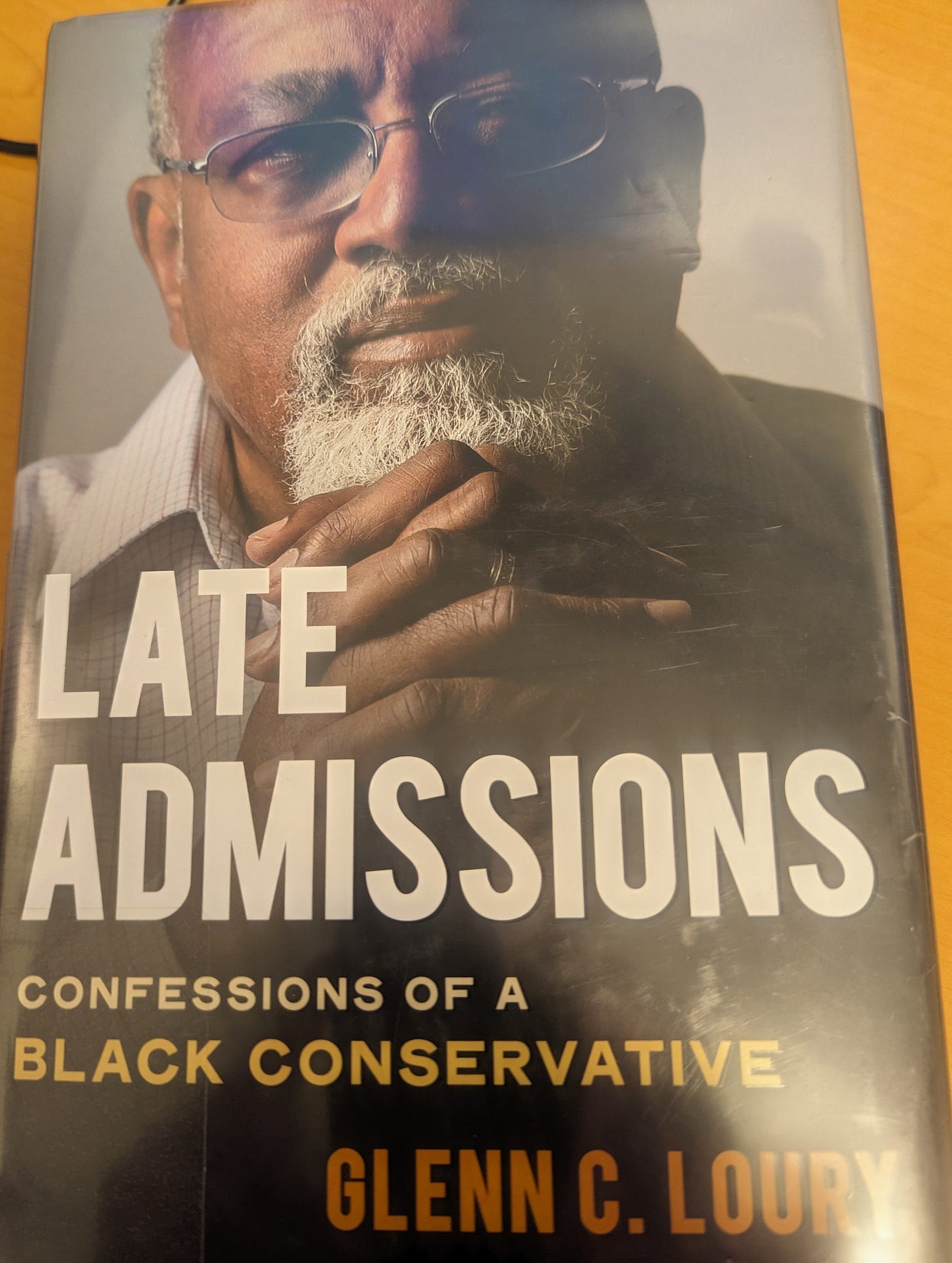

Dr. Glenn Loury’s recent 400+-page memoir, Late Admissions: Confessions of a Black Conservative, consists, then, of at least three of what creative writers might call “braids.” It starts with family and other primary relationships, it explores Loury’s path of ideas and other intellectual and political interests (and there have been many with him), and then—as interesting as anything else in the book, though certainly not completely disconnected from the first two threads—there were his exploits, his indulgences. I would say “mistakes,” but perhaps that’s too strong. What I mean is his private behavior that sometimes surprised, that threatened to to undo everything he was doing publicly. His sins, in other words, and thus the book’s title.

Loury is perhaps best known these days as an Economics Professor at Brown University, a regular podcastor at the The Glenn Show (often though not exclusively with his friend, John McWhorter), and a contrarian-type voice on issues related to race. Loury’s speech has always felt black preacher-y to me: infused with passion, rhythmic, building toward something cosmic in its significance.

Often great speakers lose some of that personality on the page, though, and yet I recently told some friends of mine that of course Loury would be a better creative writer than most of us who consider ourselves to be creative writers. Well, the first half of the book, anyway. The second half felt a bit rushed at times, and Loury’s almost-exclusive telling rather than showing (basically an inability or unwillingness to write “in scene”) eventually wore me down, especially in parts that might benefit from a bit more emotion.

Loury is emotional as a speaker, and that’s some of his appeal: he’s a great thinker who also feels. And of course we don’t completely lose that on the page, especially as it relates to where he comes from, the South Side of Chicago. His parents, his uncles, his childhood friend Woody. Playing chess and hustling in pool halls and trying to score with a woman. Loury spent his adult life in very different world, though: by my count, he mentions at least eight universities he’s taught at, and every single one of them could be what we consider “elite” (Boston University, Brown, Columbia, Harvard, Michigan, MIT, Northwestern, Stanford). He also taught inter-disciplinarily: his primary field was economics, but he also taught Afro-American Studies, had an appointment in the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard, and started an institution that focused on race at Boston University.

So what is he doing, then, leaving the office and heading over to the rough part of town for some marijuana or to play chess or to smoke some crack or hook up with a prostitute? Well, addiction is its own beast, and Loury does seem to have some addictive tendencies, but at its best it seems to me that Loury was looking for something genuine: he was looking for home, for the familiar, to feel like himself in a world that was very different from the streets of the South Side of Chicago. He wanted to belong.

Sexuality is also its own beast, and Loury doesn’t try to hide that he was had kids with three different woman, two of whom he would marry and none of whom he would be faithful to. He was a serial cheater (including with his childhood best friend’s wife), and it was striking how much he was willing to risk with his behavior. In the late 1980s, he was a top target by President Reagan’s administration for the Undersecretary of Education position. Until, that is, the background checking process revealed a Boston apartment in his name that was being lived in by a 23-year-old young woman. One of Loury’s mistresses. That young woman would soon accuse Loury of a number of violent crimes after he physically grabbed, lifted, and removed her from the apartment (after, he says in the book, she bought $600 worth of clothes at a nearby shop and told the shopkeepers to track down Loury for the money).

Loury’s wife Linda would stay with him in spite of that humiliation, as well as Loury’s self-admittance to a rehab facility and then halfway house (which he was subsequently kicked out of for using before going back again to rehab). Linda is a bit of a stilted character in the whole book; she barely has a face and we hardly know anything about her, other than that there really did seem to be genuine love in the beginning, that she is an academic like he is, that the two of them had two kids together, and that she stayed through his unfaithfulness again and again. Loury mentions one poignant moment of his own grief after her death more than ten years ago when he came across a self-help book of hers about forgiveness, complete with underline passages and notes about him. Loury marries again after Linda, to the women he is now with, which ends the book, though it doesn’t even come close to feeling finished, as many memoirs (and this feels as much like an autobiography at times as it does a memoir) don’t.

Loury is now 75 years old, and with a large enough platform and network that he must not fear too much the prospect of arming his critics at the end of his life, but the obvious tension and potential contradiction in all of this is that one of Loury’s messages over the years—this will be simplified, and I haven’t read any of his technical or theoretical academic work—is that the Civil Rights political strategy for African Americans was certainly useful at one point but is now basically dead, and that parts of it are destined to keep failing, should people continue to pursue that political and cultural path. “No one is coming to save you!” he’s apt to say instead, as he advocates for better communities and culture and values. At times he comes across—to me anyway—like a black Jordan Peterson.

And yet, Loury almost ruined his life with drugs, he committed adultery who knows how many times, oh and by the way, he abandoned his first son for the first twenty years of his life (after a surprise encounter between the boy and his half sister, the two would rebuild a relationship). But here’s one thing the critics won’t be able to say about Loury’s book: that he flinched.

As I’ve said, Late Admissions is not really a linear book, but if I were to make his story as written by him linear, it might look something like this:

boy comes of age in Chicago → flunks out of first attempt at college → gets very interested in economics and starts rising while noticing he has more belief in markets than most liberals do → fathers a few kids out of wedlock and gets married for first time then tanks it in move across the country to grad school —> starts developing relationships with not just conservatives but influential Republicans → on the verge of a political appointment while making regular beelines for parts of town where he could get money and drugs → converts to Evangelical Christianity as part of his recovery from crack → start to lose his faith when he notices all the denial about illness and death in relationship to God → makes more of a liberal turn, especially around the issue of incarceration → get disillusioned with his liberal colleagues and audience again and comes back to right-leaning contrarian act → tries to salvage family

Again, that’s not perfect, but it’s in the ballpark. And as I read, while I had to cringe often, it also felt…so human. Like, Loury was looking for something. Longing for it. Who am I, and why am I here? Trying things on, throwing darts at a board.

Hmm, how do I not be poor my whole life, for starters? We’ll try the serious professional path. But whose side am I on? Let’s try the conservative thing, the liberal thing—all of this is so confusing—ahh, but the drug thing kind of feels nice, other than this shame, and oh, sex with women is nice, and then to try to clean it all up, how about the Christian thing, the attempt at family. And there are all these pressures and expectations pulling at you, and you’re stressed out and feel like you’re failing. Oh, and now one of your sons is coming out as gay, how do you feel about that? Well, try to be supportive. Now your wife, the one who stayed through all your infidelity, is dying.

And at the end of it, what is left? What stands? What matters? Ecclesiastes kinds of questions. And after reading his book, I’m not really sure what Loury’s answers to those questions are, but again, I don’t really blame him for that. This life is confusing as hell. Even though so much of our lives are contained and spent by trying to figure out what we “believe,” so much of it fails us, disappoints when we need it the most. In Loury’s case more than most, certainty and conviction is such a tough thing to lose because he was so talented at presenting any number of ideas:

“These performances—for that’s what they were—left me feeling exhilarated, enamored of my own abilities on the stage, and intoxicated by the affirmation of the crowd. But late at night, when the adrenaline wore off and there was no one around to shake my hand, slap me on the back, and thank me for my ‘truth-telling,’ I began to question just what it was I was doing up there. I loved the high I got from speaking in this way and receiving the adoration of these strangers, the nods of affirmation I received from other African Americans who encouraged me to keep going out there and telling the truth. But was I doing this because I was a truth-teller or because I loved the feelings I got from playing the role of the truth-teller?”

When Loury’s wife is dying, and he’s having a hard time being present for it, one of his sons asks him why he’s gone so much, why he’s not standing up in this difficult time. “Because I’m bored,” he admits. This is the part in life where my wife dies. And ‘What in the world are we doing here; what does any of it mean?!’

This will be too simplified, too, and I have no right to psychoanalyze Loury—though I do think he’s searching for a gear that he wants to have but doesn’t quite feel like he does—but I did think while reading about a scene in the 2017 movie, Molly’s Game. Molly had lost a skiing career due to injury and then got in all kind of trouble (and basically lost everything) while running illegal poker games. Her father is a therapist played by Kevin Costner. Toward the end of the movie, he tracks her down at an outdoor skating rink, where he says (with some back-and-forth dialogue left out):

“Alright, we’re going to do three years of therapy in three minutes…I’m gonna do what patients have been begging therapists to do for a hundred years. I’m just going to tell you the answers…Why does a young woman who, at 22, has a gold-plated resume, why does she run poker games?…You were going to be a success at anything you wanted, and you know it…Why did you do the other thing instead?…You didn’t start with the drugs until the end. They weren’t the problem, they were the medicine. It was so you could control powerful men. Your addiction was having power over powerful men…It’s because I knew you knew…That I was cheating on mom…You’ve known since you were five. You saw me in my car, and you really didn’t know what you saw. You knew, honey, and I knew you knew.”

I said Loury doesn’t really write in scene, and he doesn’t—and also, one of the more compelling “scenes” in the book is that of young Loury trying to be a “Player” (this is language he uses throughout the book to describe his own motives and actions) in a pool hall when his mother walks in with one of her own men (who wasn’t his father or her known partner). His mother would marry multiple times, like her son, and when her daughter, Glenn’s sister, came out of her body it was obvious to anyone who looked that the child was not Glenn’s father’s daughter.

We can probably make too much of these kinds of events in our lives, use them as an excuse, and so perhaps it’s to Loury’s credit that he doesn’t hang all or a lot of his behavior on what he saw from his mother. And yet, the subconscious is such a mysterious mechanism. It can drive our behavior while depriving of us our motivation. And so, by the end of Linda’s life—she died of cancer, by the way, and it doesn’t seem like a completely ridiculous question to ask how much of her inward “acceptance” of her husband’s behavior might have been connected to her body’s attacking itself—there was Glenn, still struggling to embrace the vulnerability of his dying wife’s pain. Putting head phones on during her last night so that he didn’t have to hear her struggle.

I do not say that, believe it or not, to condemn or to sit in judgement. Loury himself laid it all out for us, and I loved the book, as I have often enjoyed hearing him speak. But the book’s content also disturbed me in a way that will likely haunt me for a long time. This is probably the case more often than we'd like to think, but perhaps this man has been talking primarily to himself all along.